John Coltrane passed away on July 17, 1967, aged only 40 years old. At that time, San Francisco was in the throes of the Summer of Love. By many accounts, that summer was actually akin to a bad comedown following the success of earlier celebrations like that January’s Human Be-In. Joan Didion called it “social hemorrhaging.” George Harrison said he quit taking L.S.D. after walking through the Haight in August of 1967. However, the musical explosion that centered in San Francisco and both fed off and spurred on that summer’s suspect energy is well documented as a landmark development in American pop culture, and, to me, does a lot to redeem the era, despite the escapist vibe of the flower children who descended on the city en masse.

Yet perhaps less well known is how, in the years before psychedelic rock n’ roll fully took off, San Francisco was a crucible for Coltrane and his own style of mind-expanding music, all the while inspiring the long-hairs who followed him. Piecing together his live appearances, recording dates, and the groups he brought with him in San Francisco reveals that during Coltrane’s last period, the city was, coincidentally or not, a repeated inflection point on his musical journey, which was progressing at a breakneck speed right up until his death.

But first, for some context: when people think of Coltrane’s last period, they probably think of the powerful, noisy, and free performances that came in the last two years of his life, following the release of his blockbuster album A Love Supreme in early 1965. To me, it’s actually not so easy to pinpoint his transition from conqueror of hard-bop (like on Giant Steps) to otherworldly avant-garde explorer (like on Interstellar Space). To complicate matters, while A Love Supreme stands as Coltrane’s statement of intent to communicate musically his deep spiritual re-awakening, in a way that would eventually alienate many fans and critics, the album is also his crowning mainstream success, suitable to play in a Starbucks store, and likely to be recognized by the patrons therein.

As early as 1961, you can hear Coltrane pursuing atonal ideas on tunes like “India,” recorded live in November of that year and issued on the 1963 album Impressions.

“India” live at the Village Vanguard

But he then followed this with accessible collaborations with elder statesman Duke Ellington and crooner Johnny Hartmann, partly at the wish of his record label. And in June 1965, just weeks before he got together a big band of the finest free jazz players of the time to make one of his most out-there recordings, the album length “Ascension”, Coltrane recorded material with only his classic quartet of McCoy Tyner (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass), and Elvin Jones (drums) that didn’t stray too far from their approach, albeit a groundbreaking one, since forming in 1962.

However, by late summer 1965, Tyner and Jones, and their hesitancy to move beyond traditional hard-bop foundations, were acting more and more as constraints on Coltrane’s increasingly free playing style. So after the quartet opened a two-week gig on September 14, 1965 at the Jazz Workshop in North Beach, and then left town with a new addition to the group, one Pharaoh Sanders on tenor saxophone, Coltrane fully crossed the Rubicon in the direction of all-out free improvisation.

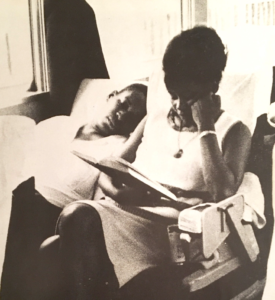

Coltrane, Sanders (standing), and the rest of the last quintet.

Today, Sanders is a legend across genres, and still performs his groundbreaking style of free spiritual jazz, which fuses traditional African and “Eastern” influences with the avant-garde. According to Lewis Porter’s indispensable John Coltrane: His Life and Music, Sanders and Coltrane first met in 1959 in Oakland, where Sanders was living and Coltrane was passing through with Miles Davis. After Sanders moved to New York a couple of years later, the two stayed in touch, and Sanders sometimes sat in with Coltrane, while also working up the reputation to record his first album as a bandleader in 1964. Sanders played on “Ascension” in June of 1965, but it wasn’t until those September gigs at the Jazz Workshop that he became a permanent member of Coltrane’s group. And it appeared to have happened quite casually. Sanders, who was living in the city at the time, was in the audience for some of the shows, and then sat in at Coltrane’s request for the remainder. Instead of a formal invitation to join the group, by some accounts Coltrane merely gave Sanders the address of the next gig in Seattle, and trusted that he would take the hint.

Those two weeks in San Francisco marked the end of the much-acclaimed classic quartet as both a performing and recording unit (they had some brief studio time at Coast Recorders near Union Square on September 22). The quartet’s last full sessions before this West Coast tour, as heard on First Meditations (for quartet), certainly showcase Coltrane’s growing disinterest in swinging rhythms and traditional harmonic structures. However, with Sanders, Coltrane’s performances quickly lifted off into another dimension and stayed there, as documented on the classic Live in Seattle, recorded just 4 days after the group left San Francisco. Pure sonic expression reigns, with ecstatic shrieks and honks central to the music, not merely secondary as embellishments or imperfections.

In the remaining months of 1965, Coltrane worked at a furious pace performing and recording trademark albums of his later years, like Om, Kulu Sé Mama, and Meditations, before returning to San Francisco in January 1966. During this visit, the city would once again be the site of important developments in Coltrane’s last period—namely, Alice Coltrane’s debut with the group, and Elvin Jones’ brusque departure.

The Stanford Daily, January 24, 1966

The Coltrane Quintet was booked to play with the Thelonious Monk Quartet at Stanford University on January 23, 1966, followed by another two-week gig at the Jazz Workshop in North Beach. The group that showed up with Coltrane to Stanford’s Memorial Auditorium actually totaled eight, surprising the mid-afternoon crowd with an octet featuring Alice Coltrane on piano, Sanders on tenor, two drummers (Jones and the late ’65 addition Rashied Ali), two bassists (Garrison and Donald Garrett), and percussionist Juno Lewis, composer of “Kulu Sé Mama.” Newspaper reports of this show, Mr. and Mrs. Coltrane’s first together, took an awe-struck but receptive tone in response to what was surely a fierce performance of a jazz ensemble at the frontier of the genre. One notable exception, however, was the review in Stanford’s student paper, ultimately suggesting that, contrary to 1960s lore, the college students didn’t always know best. The student critic was unable to view Coltrane’s new sound as “American jazz in any recognizable form”, and rather offensively labeled it simply “African music” influenced by the way Coltrane and his group “have been hated and have learned to hate, sociologically.” Clearly, someone had missed the memo on A Love Supreme.

From the San Francisco Chronicle, January 1966

Coltrane then moved on, albeit without The Stanford Daily’s blessing, to his two-week gig at the Jazz Workshop starting January 25, 1966. In advance, The San Francisco Chronicle advertised that the group would be a quartet, continuing what seems to have been a pattern of Coltrane’s recently expanded ensemble surprising audiences both by its size and the music it performed.

Not long into the gig, Elvin Jones, Coltrane’s longtime drummer and a respected force of nature in his own right, would surprise everybody by leaving the group for good. As with Tyner, who quit Coltrane’s group just a month before, Jones reportedly respected, but couldn’t relate to, the direction Coltrane’s music had taken. Both Tyner and Jones would tell interviewers that by the end of 1965, they couldn’t hear themselves over the intense back and forth of Coltrane, Sanders, and the second drummer Ali, whose freewheeling playing better complemented the saxophonists’ chaotic exchanges. Tellingly, Jones flew straight to Germany to tour with the venerable, 65-year-old Duke Ellington, effectively leaving a trailblazing jazz icon in Coltrane and joining one in the midst of a victory lap around the world.

Yet more importantly for Coltrane’s sound in the last years of his life, and his legacy after passing away, was that these San Francisco performances marked the debut of Alice Coltrane with the group. Alice Coltrane’s genius of spiritual expression through music, on par with her husband’s, has been long under-appreciated. Recently, she has posthumously been receiving wider recognition, with the help of archival releases of devotional music she made during her years as leader of an ashram, decades after her husband’s death.

The Coltranes in Japan, 1966. Photo: Kazuo Arai.

Alice had become an accomplished pianist since getting her start playing in churches in Detroit, moving onto various touring jazz groups, and spending time in Paris with the great bebop pianist and composer Bud Powell and his family. John and Alice met in 1963 in New York City, when she was on tour with the Terry Gibbs Quartet. They married after John secured an amicable divorce from his first wife, Naima, in late 1965. McCoy Tyner’s departure then prompted Alice to join her husband on stage as the pianist in his group. It is worth marveling at how Alice so naturally meshed with the new direction her husband’s music had taken by early 1966—or perhaps it should come as no surprise, given their deep connection off stage. But before the San Francisco shows, Alice had not been performing for some time due to the birth of two of their three children together. And, her recorded output prior to joining the Coltrane group barely suggested the masterful accompaniment she would come to provide for her husband’s free music in his last two years—but this could easily be due to the limited opportunities to record and perform that were afforded women in jazz at the time. Indeed, an early example of her playing, on this 1957 single by The Premiers, a Detroit vocal group, does include flourishes that call to mind the distinctive, harp-inspired, playing style that became her trademark.

With his longtime drummer gone and his wife on board, Coltrane had effectively assembled the core quintet that he would perform with until his death: Sanders on saxophone, Garrison still on bass, Alice on piano, and Rashied Ali on drums. Others would often sit in too, swelling the group to as much as a nonet (nine musicians!).

During this visit to San Francisco, Coltrane also managed to return to the Coast Recorders studio, providing us with a snapshot of the new quintet just days after their first live performances together. “Reverend King” and three other numbers were recorded at this session but not released until 1968. “Reverend King” starts with a recitation of the Buddhist mantra “Om Mani Padme Hum” over Alice’s mellow piano fanfare, before the rest of the players enters. Sanders and Coltrane gorgeously build in intensity towards a furious blast of noise that persists for much of the recording before relenting and reintroducing Alice’s gentle playing and the mantra. The recording then concludes with the recitation of a simple prayer: “May there be peace and love and perfection throughout all creation”. Despite its free structure and lack of a swinging backbeat, the music has a recognizable circularity, leading the listener from opening invocation to expressive crescendo, and back to the familiar calm of the invocation. It is revelatory to hear, as Lewis Porter puts it, Coltrane “devoted relentlessly to the exploration of abstract ideas”. To see this music performed in a small club like the Jazz Workshop would have been nothing short of transcendent.

After San Francisco, Coltrane’s last quintet would elicit rave reviews and harsh receptions in almost equal shares. By this time, the widely read jazz magazine Down Beat had even started assigning two reviewers for each of Coltrane’s releases, reflecting the contentiousness of this new music. Coltrane would continue performing with this quintet throughout 1966, including during his legendary trip to Japan, where, by many accounts, he was received as a superstar. The quintet’s first stop after Japan was again San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop in late-July 1966, just two days after their last gig in Tokyo. How different, and likely welcoming, the tiny North Beach club must have felt for the players, who had just spent two weeks playing festival halls across Japan.

Coltrane’s flurry of activity in San Francisco during his last years is also representative of San Francisco’s lost standing as the destination for jazz musicians outside of New York, which seems to have peaked during these post-Beat, pre-Hippie years. During his San Francisco visits, Coltrane had esteemed company: In September 1965, Duke Ellington was just up the hill from the Jazz Workshop at Grace Cathedral, performing his first Sacred Concert, and reportedly coming down to see Coltrane perform at night. In January 1966, Archie Shepp, a younger favorite of Coltrane’s at the forefront of the jazz avant-garde, was across town at the Both/And Club recording his classic Live in San Francisco, and would let members of his band sit in with the Coltrane quintet over in North Beach.

The quintet was booked but failed to return to San Francisco in April 1967. By this time, Coltrane’s latent liver cancer had forced him to basically retire from live performance. This was just around the time San Francisco’s hippies and hoppers were peaking before the Summer of Love.

For a city that can appear to be changing in all the wrong ways today, it is at once comforting and deflating to know that 50 years ago, San Francisco was frothy with musical adventure, serving as Coltrane’s launching pad for his transformed music, and then just a few years later as the proving ground for artistic expression of a whole different kind with rock n’ roll bands that took Coltrane’s playing as inspiration for their musical explorations. Let’s hope we in the city today can go forward with some of that enthusiasm in mind!

// jamie aylward.

Coltrane lives on in San Francisco at the Saint John Coltrane A.O. Church on Turk Street; a visit is encouraged!

Bibliography and further reading: - John Coltrane: His Life and Music by Lewis Porter (1998) - The John Coltrane Reference by DeVito et. al (2008) - Jazz Puzzles, Pleases in The Stanford Daily, Volume 148, Issue 65 - George Harrison in the Haight - Fun, Yes, But Music? by Ross Cole (2012) - When Bebop Filled the Night by Art Peterson (2011)